ON CALL NEURO

ON CALL NEURO aims to provide residents with a quick “guide” to handling neurological cases and consults while on service or on call.This guide is not a replacement for understanding concepts in neurology in depth. However, it does provide a quick summary of pertinent clinical information and a reference for management algorithms and treatment options.This website's intended audience is for medical providers for educational purposes only. It is not meant to be used as medical advice for the general public. Please see the disclaimer for further information.If you have any feedback for the website, please fill out the survey here.

Approach to...

COMING SOON

Approach to... is a new section that will provide approaches to various undifferentiated cases (e.g. weakness, dizziness, and diplopia) Check back soon for when this section launches.

Headache

Important to rule out secondary headache causes from primary headache disorders using SNOOP4

| Clinical Features | Differential Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|

| S | Systemic symptoms (e.g. weight loss, fevers) | Malignancy, infections, GCA |

| N | Neurological symptoms (e.g. focal neurological symptoms, confusion vision loss) | Structural lesions, strokes, encephalitis |

| O | Older age (Over 50) | Mass lesions, GCA |

| O | Onset ("Thunderclap" like, maximal intensity in less than a minute) | Vascular causes (e.g. SAH, RCVS, hemorrhagic stroke) |

| P | Papilledema | Raised ICP (IIH) |

| P | Pregnancy | Pre-eclampsia, CVST, RCVS |

| P | Positional (e.g. worse with Valsalva or worse from supine to sitting) | SIH, CVST, mass lesions |

| P | Pattern change (change in headache pattern or quality) | Assess other secondary causes |

Migraines & Tension Headaches

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski and Dr. Caz Zhu

Reviewed by Dr. Will Kingston

Migraines

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Activation of trigeminal vascular system and cortical spreading depression

Affects people in their peak productive years. Second most disabling condition, second only to low back pain

More common in females, strong family history present

Clinical Features

5 or more attacks

Lasting 4hrs to 3 days

With 2 of the following: unilateral, pulsating/throbbing quality, moderate to severe intensity, worse with activity

With 1 of: photo/phonophobia or nausea/vomiting

Aura lasting 5 to 60min before headache onset, accompanied or followed by headache within 60min. Symptoms of aura are fully reversible and can present as sensory (e.g. numbness/parasthesias), visual, speech and/or language, motor, or brainstem (rare) features

⊙ CLINICAL PEARL

Three best clinical clues to diagnosis migraines: PIN the diagnosis - Photophobia, impairing, and nausea

Investigations

Neuroimaging is needed if red flags are present

Unusual, prolonged, or persistent aura

Increasing frequency, severity, or change in migraine clinical features unless change in pattern (i.e. medication overuse headache)

First or worst migraine

Migraine with brainstem aura

Confusional migraine

Hemiplegic migraine

Late-life migrainous accompaniments - acephalgic migraine

Migraine aura without headache

Side-locked migraine

Post-traumatic migraine

Treatment

Abortive therapy: NSAIDs (e.g. Ibuprofen, Naproxen 250-500mg p.o. with PPI, Cambia 1 sachet p.o.), Tylenol, triptans, Mg can be taken with aura to try and reduce its duration and severity, Ubrogepant (CGRP antagonist) - 50-100 mg daily is a new approved medication for an abortive agent (side effects: nausea, drowsiness)

Acute therapy in the ED: normal saline 2-3L IV bolus (ensure no CHF), metoclopramide 10mg IV (check QTc interval), Mg 1g IV, Ketorolac 15-30mg IV, DHE 0.5mg IV with metoclopramide and if tolerated can receive 1mg as next dose (contraindicated if triptan use within 24 hours; check QTc interval)

Preventative therapy: started when >4 headache days/month and/or no response to acute therapy, and the choice depends on comorbidities and symptoms

CGRP antagonists can be considered in outpatient follow-up as a preventative therapy

Lidocaine nerve block (+/- methylprednisone) acts as both acute and preventative therapies

Nutraceuticals: Mg 300-600mg qhs, vitamin D 1000-2000IU, riboflavin 400mg, coenzyme Q10 300mg daily

Non-pharmacological therapy: reduce lifestyle triggers, relaxation/meditation, massage, exercise, reduce caffeine intake, increase hydration, protein-rich diet (especially breakfast), Cephaly device, mindfulness

Medication overuse headache (>15 days/month of NSAID/Tylenol use and/or >10 days/month of triptan use) therapy: discontinue NSAIDs/Tylenol, attempt to break the headache cycle with a longer acting NSAID (e.g. Anaprox 550mg BID or Naproxen 250-500mg BID) x1-2 weeks

Note: Lidocaine nerve block (+/- methylprednisone) and Botox injections act as both acute and preventative therapies

TRIPTANS

| Triptan | Medication Dose | Uses | Side-effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almotriptan | 12.5mg p.o | Good for patients with significant side effects from previous triptans | Lowest side-effect profile; Mild stiffness |

| Sumatriptan | 25-50mg p.o, 5-10mg intra-nasal, 4-6mg SC | Nasal options are best for patients with rapid onset/wake-up headaches; Only triptan with an injectable option | Bad taste, burning sensation (intra-nasal and SC), tingling, injection site reaction, nausea/vomiting |

| Rizatriptan | 5-10mg p.o./MLT | MLT option is useful for patients with strong components of nausea | Lowest risk of medication overuse headaches;; Dizziness, somnolence, dry mouth, asthenia |

| Zolmitriptan | 2.5-10mg p.o./MLT, 5mg intra-nasal | MLT option is useful for patients with strong components of nausea; Nasal options are best for patients with rapid onset/wake-up headaches | Nausea/vomiting, paraesthesias, somnolence, nasal discomfort |

| Frovatriptan | 2.5mg p.o. | Menstrually-related migraine (used on day -2 or -3 of menses) | GI upset, nausea/vomiting |

| Naratriptan | 2.5mg p.o. | Menstrually-related migraine (used on day -2 or -3 of menses) | GI upset, nausea/vomiting |

| Eletriptan | 40mg p.o. | - | Lowest risk of Medication overuse headaches; Dizziness, somnolence, dry mouth, asthenia |

Contraindications of triptans:

MAO inhibitor within 2 weeks

CAD, vasculopathy, PVD

Cardiac arrhythmia

Recent stroke

Uncontrolled HTN

Renal disease

Anaphylaxis to triptans previously

Hemiplegic migraine

Migraine with brainstem aura

Intake of ergots or triptans within 24 hours

PREVENTIVE MEDICATIONS FOR MIGRAINES

| Medication | Dose | Considerations | Side-effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candesartan | 2mg p.o. daily with up-titration by 2mg weekly (maximum 16mg/day) | Comorbid HTN; Contraindicated in pregnancy | Hypotension, dizziness |

| Propranolol | 40-80mg p.o daily and uptitrate up to 240mg/day | Avoid in patients with asthma or heart block; Comorbid anxiety | Hypotension, dizziness |

| Gabapentin | 300mg p.o. daily/TID with up-titration by 300mg weekly targeting 1200-1500mg/day divided TID (max 1800mg/day) | Avoid in renal failure; Sleep disturbances, mood, neuropathy | Drowsiness, dizziness |

| Topiramate | 15-25mg p.o. daily with up-titration by 15-25mg q1-2weeks targeting 100mg qhs or 50mg BID (max 200mg/day) | Comorbid mood disturbances; Contraindicated in pregnancy | Nephrolithiasis, acute closure glaucoma, dizziness, tremor, cognitive slowing, weight loss |

| Nortriptyline | 10mg p.o. Qhs with up-titration of 10mg q1-2weeks targeting 20-40mg daily (maximum 150 mg/day) | Sleep disturbances, mood | Weight gain, drowsiness, increased seizure threshold |

| Amitriptyline | 10mg p.o. Qhs with up-titration of 10mg q1-2weeks targeting 20-40mg daily (maximum 150 mg/day) | Comorbid anxiety/depression | Weight gain, drowsiness, increased seizure threshold |

| Atojepant | 5mg/kg p.o. daily | - | Constipation, nausea |

CGRP antagonists (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab) are options for treating migraines as well - although currently, indicated for patients who have headaches ≥ 8 headache days/months and have failed or are intolerant to ≥ 2 preventative agents. Side effects of CGRP antagonists include constipation, injection site reaction, and hypertension (erenumab).

Patient Education

Encourage patients to keep track of the frequency and intensity of their migraines (Migraine Tracker app)

Patients should be taking abortive therapies EARLY (as soon as they feel like they are getting their migraine) to prevent central sensitization

If their migraines continue to persist - they can take another NSAID or triptan in another 2 hours

Not all triptans are effective for everyone; just because one triptan is not effective does not mean another will not be for the patient

If a patient still experiences high intensity of migraine after taking a triptan, a second dose can be taken 2 hours after the first dose (maximum 2 doses in 24 hours)

Preventative therapy can take 2-3 months to see benefits and often can be up-titrated as tolerated

Treatment of comorbid conditions (e.g. depression) is important

Tension Type Headaches

Important to note that many people diagnosed with tension type headaches are mis-diagnosed migraines

Clinical Features

Can last hours to days

With 2 of the following: bilateral, pressing/tightening (non-pulsatile), mild or moderate intensity, not worse with activity

No more than 1 of photophobia, phonophobia, or mild nausea

Considered a chronic tension type headache if it occurs < 15 days a month or > 3 months

If a patient presents to the physician/hospital with TTH, re-think the diagnosis

Investigations & Treatment

See above section for migraines

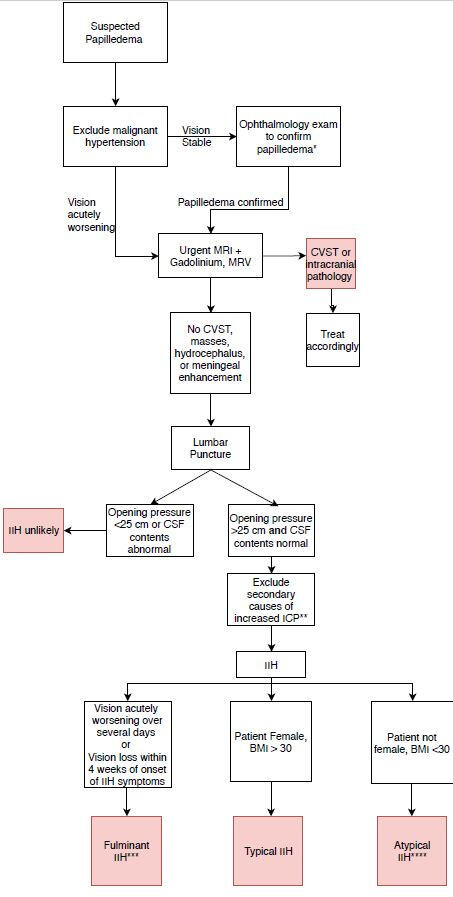

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

By Dr. Kia Gilani

Reviewed by Dr. Jonathan Micieli and Dr. Will Kingston

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Raised ICP without the presence of a space-occupying lesion

Thought to be related to reduced CSF absorption

More common in females of child-bearing age

Clinical Features

Headache

Transient visual obscurations - unilateral or bilateral greying of vision or dark spots that are worse when bending over or Valsalva

Blurry vision

Horizontal diplopia - CN6 palsy

Reduced visual acuity in some (less common)

Pulsatile tinnitus

Back and/or neck pain

Radicular pain

Cognitive disturbance

ICHD criteria for Headache attributed to IIH

New headache or significant worsening of pre-existing headache

Both of: IIH diagnosis, and CSF opening pressure >25 cmH2O

Either of: headache developed or significantly worsened in relation to IIH or led to its diagnosis; headache accompanied by either or both of pulsatile tinnitus, papilledema

Not better accounted for by other ICHD-3 criteria

Click image to enlarge

Must rule out secondary causes of increased ICP

CVST

Medications: antibiotics (tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones), vitamin A derivatives, lithium, thyroxine in children, corticosteroids

SVC obstruction (very rare)

Associations with IIH:

Endocrine: PCOS, Cushing’s, Addison’s, hypoparathyroidism, hypothyroidism

Polycythemia, anemia

Uremia and/or renal failure

OSA

SLE

Down’s syndrome, Turner’s syndrome

Investigations

CBC

MRI/MRV brain or acutely CT/CTV brain if MRI unavailable

Consult/refer to Ophthalmology

Lumbar puncture with opening pressure in supine position

Blood pressure

Common neuroimaging findings in IIH

Optic nerve tortuosity

Enlarged optic nerve sheath

Flattened posterior globe

Intraocular protrusion of optic nerve head

Empty sella

Bilateral transverse sinus stenosis

Slit-like ventricles

Acquired tonsillar ectopia

Treatment

Weight loss; consider referral to bariatric clinic

Low sodium diet

Acetazolamide 500mg p.o. BID (up to 4000mg/day) - titrated by Ophthalmology based on degree of papilledema and visual function

Topiramate

Discontinue offending agent if present; treat underlying cause if present

Management of comorbidities (i.e. OSA)

Surgery in fulminant cases: VP shunting, optic nerve sheath fenestration, sinus stenting

Patient Education

Treatment is aimed at visual sparing and persistence of headache should not be considered treatment failure

Patients should be counseled on the importance of weight loss, as it is the most common risk factor and the only disease modifying treatment available

The importance of adequate follow up should be emphasized, as untreated IIH can cause permanent vision loss

Up to 40% of patients may have recurrence

Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension

By Dr. Caz Zhu

Reviewed by Dr. Will Kingston

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Caused by CSF leakage, diagnosis requires presence of low CSF pressure and/or evidence of CSF leak on imaging

Female predominance (2:1) and in patients in their 30-50's

Clinical Features

Orthostatic headaches (develops when upright and improves with lying supine) - orthostatic features may disappear if SIH has been longstanding

Other symptoms include: nausea/vomiting, hypoacusis, neck stiffness/pain, tinnitus, other neurological symptoms if due to downward displacement of the brain (e.g. diplopia, gait changes)

Can also be seen in unexplained coma

ICHD criteria for Headache attributed to SIH

Headache fulfilling criteria for 7.2 Headache attributed to low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure (see below)

Absence of a procedure or trauma known to be able to cause CSF leakage (Cannot be diagnosed within 30 days of a spinal tap)

Headache has developed in temporal relation to occurrence of low CSF pressure or CSF leakage, or has led to its discovery

Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

Headache attributed to low CSF pressure

Either or both of the following:

Low CSF pressure (<60 mm CSF)

Evidence of CSF leakage on imaging

Investigations

MRI/MRV brain and spine

Consider CT Myelogram or Digital Subtraction Myelography - helpful to localize CSF leak

Lumbar puncture with opening pressure in supine position (may not be necessary if enough clinical suspicion)

Common neuroimaging findings in SIH

Subdural collections

Enhancement of pachymeninges

Engorgement of venous structure

Pituitary enlargement

Sagging of brain (can ask radiology to look specifically for mammilopontine distance)

Subdural collection and hematomas

Treatment

Conservative: Bed rest, hydration, NSAIDs, caffeine

Epidural blood patch or fibrin glue patch (intrathecal infusion of 20 - 130 cc of blood) - will need to consult anesthesiology - however only 1/3 patients respond to first patch

Surgical referral if three failed blood patches

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

By Dr. Caz Zhu

Reviewed by Dr. Will Kingston

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Male to female predominance (3:1) only in cluster headaches

Unclear pathophysiology - thought to be related to trigeminal autonomic reflex (trigeminovascular system, occipital nerves, thalamus and hypothalamus)

Most causes are primary but important to rule out secondary causes of cluster headaches including vascular & masses (carotid artery dissections, cavernous meningioma, pituitary adenomas)

More pituitary lesions seen in people with cluster headaches

Clinical Features

Often side-locked headaches with unilateral autonomic symptoms (lacrimation, red eye, ptosis/eye edema, nasal congestion, sweating/flushing)

Associated with restlessness/agitation (banging head on wall, rocking), not able to sit still during an attack

Four common TACS:

| TACS | Cluster Headaches | Short-lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform headache attacks with Conjunctival injection and Tearing (SUNCT) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | Unilateral side-locked headaches, “suicide headaches”, often “wake-up” headaches and occur seasonally | Prominent autonomic symptoms, +++ frequent and short-lived |

| ICHD-3 | At least 5 attacks that are severe, unilateral orbital/supraorbital, temporal pain lasting 15-180 minutes; unilateral autonomic symptoms and/or restless or agitation; occurring every other day - 8 attacks/day | At least 20 attacks that are moderate - severe pain in orbital, supraorbital, temporal, trigeminal distribution lasting 1 - 600 seconds as stabbing/saw-tooth pattern; unilateral autonomic symptoms; occurring once a day up to half the time |

| TACS | Paroxysmal Hemicrania | Hemicrania Continua |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | Similar to cluster headaches but shorter and less restlessness. Responds to indomethacin | Constant, side locked headache, occasional migrainous features due to constant nature. Responds to indomethacin |

| ICHD-3 | At least 20 attacks that are severe, unilateral, orbital, supraorbital, temporal pain lasting 2 - 30 minutes; unilateral autonomic symptoms; occurring 5 attacks/day or more than half the time; attacks prevented by indomethacin | Unilateral headache that is present for more than 3 months with exacerbations of moderate/great intensity, can be remitting (pain remission for 1 day) or unremitting (no pain remission for 1 day for at least 1 year), attacks prevented by indomethacin |

Investigations

MRI brain with sella views +/- vascular imaging (MRA)

Hormonal testing - testosterone

Sleep study

Treatment

Cluster Headache treatment classified as abortive, transitional, and preventative treatment

| Abortive Therapy | Transitional Therapy | Preventative Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| High flow oxygen (12-15 L/NRB), Intranasal Zolmitriptan 5-10 mg, Intranasal Sumatriptan 20 mg, Intranasal lidocaine | Suboccipital steroid injection, Corticosteroids (prednisone/dexamethasone), Naratriptan, possibly IV corticosteroids for refractory cases | Galcazemuab, Level C evidence but verapamil, lithium, warfarin, melatonin, and gabapentin (high dose, non-invasive vagal nerve stimulation |

Paroxysmal Hemicrania and Hemicrania Continua: Indomethacin (up to 75 mg TID) and/or Melatonin

Indomethacin trial: Start with 25 mg TID for 1 week, then increase by 25 mg TID per week until final dose of 75 mg TID. If headaches are eliminated, then slowly remove one tablet per week until you reach the lowest effective dose for headache improvement. PPI is also recommended.

SUNCT: Lamotrigine is 1st line, then topiramate, gabapentin/pregabalin, verapamil, methylprednisolone

Secondary causes of cluster headaches: Medical or surgical treatment of lesion can improve headaches

Trigeminal Neuralgia

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Reviewed by Dr. Will Kingston

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Must rule out post-herpetic neuralgia

Usually middle age, females affected more

May be secondary to MS lesions (especially if bilteral)

Clinical Features

Greater than or equal to 3 attacks

Recurrent sudden onset paroxysmal attacks lasting <2min that are severe, described as electrical shocks, shooting, sharp pain

Affecting the greater than or equal to 1 trigeminal nerve distribution unilaterally (V2 and V3 are more common than V1)

Pain with innocuous stimuli (eating, brushing teeth, shaving, wind blowing on face)

Refractory period: period of time where repetitive innocuous stimuli do not aggravate the attack; not a feature in TACs

Investigations

Can consider MRI brain with trigeminal nerve protocol to visualize is there is any vascular compression of the nerve

Treatment

Acute treatment in the ED: Phenytoin 15 mg/kg IV over 30 minutes or Lacosamide 100 mg IV

Carbamazepine 200-1200 mg/day

Gabapentin or Pregabalin

Gamma knife radiosurgery (if refractory to medical treatment)

Surgical decompression of nerve if evident pathology

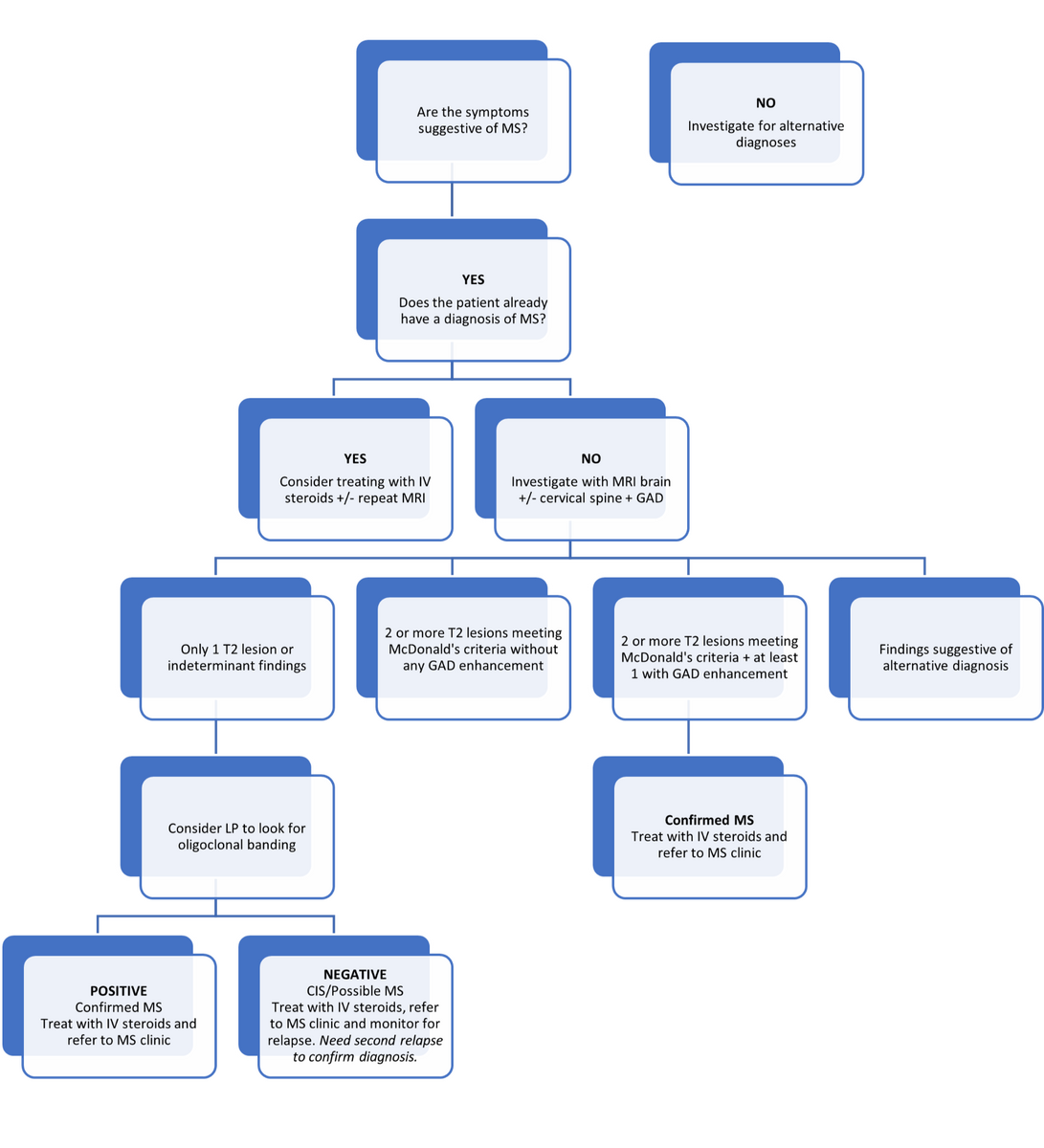

Demyelinating disease

Multiple Sclerosis

By Dr. Jane Liao

Reviewed by Dr. Alex Muccilli

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Chronic inflammatory disease of the CNS with evidence of demyelination and axonal damage

Mean age of onset 30 years (40 years with PPMS), affecting female : male 3:1

Risk Factors

Latitude - further from equator, greater risk; when a patient immigrates from their country of origin after 15 years old, they maintain the MS risk from the country of origin.

Low vitamin D levels and sunlight exposure

Genetics - HLA DRB1

Smoking

Adolescent obesity

Vitral triggers - EBV

For Poor Prognosis Factors for MS, see Figure 1 in this article: Reaching an evidence-based prognosis for personalized treatment of multiple sclerosis

Diagnosis of MS requires evidence of dissemination in time and dissemination in space (McDonald Criteria) through a combination of clinical and radiographic criteria

Criteria are meant to be applied to a patient presenting with symptoms consistent with CNS inflammatory demyelinating disease

NOT meant for patient with incidental MRI findings

Imperative that alternative diagnoses are considered and excluded (particularly NMO/MOG in the right contexts)

An attack/relapse/exacerbation: symptoms or signs typical of an acute inflammatory demyelinating event (current or historical) with duration at least 24 hours, in absence of fever or infection

Radiologically speaking:

Dissemination in Space (DIS): 1 or more T2 lesions in at least 2 of 4 areas (periventricular, juxtacortical, infratentorial, spinal cord)

Dissemination in Time (DIT): A new T2 and/or gadolinium enhancing lesion on follow up MRI (at least 30 days after presentation) OR simultaneous presence of asymptomatic gadolinium-enhancing and non-enhancing lesions at any time

The diagnosis can be made with:

History of 2 or more attacks and objective clinical evidence of 2 or more lesions (or objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion with reasonable historical evidence of a prior attack)

2 or more attacks but only objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion: demonstrate DIS as above or await further attack involving a different CNS site

1 attack and objective clinical evidence of 2 or more lesions: demonstrate DIT as above or await second clinical attack

1 attack and objective clinical evidence of 1 lesion (CIS): must demonstrate DIS and DIT as above or await second attack

CSF studies positive for OCBs can be used as a surrogate for DIT if the DIS criteria are met to make a diagnosis

Subtypes of MS

Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS): one clinical attack with corresponding MRI finding, but does not fit dissemination in time or space criteria

Relapsing remitting MS (RRMS): most common (80%); discrete clinical relapses with resolution of symptoms back to baseline in-between attacks

Primary progressive MS (PPMS): progression of disease from onset with variable degree of recovery; stable between episodes of PPMS

Secondary progressive MS (SPMS): initially beginning as RRMS, patients continue to have clinical attacks with less and less baseline recovery in-between attacks

Clinical features

Symptoms of MS can vary but common presentations of MS include:

Optic neuritis - reduced visual and color acuity, blurry vision, and pain with extraocular eye movements

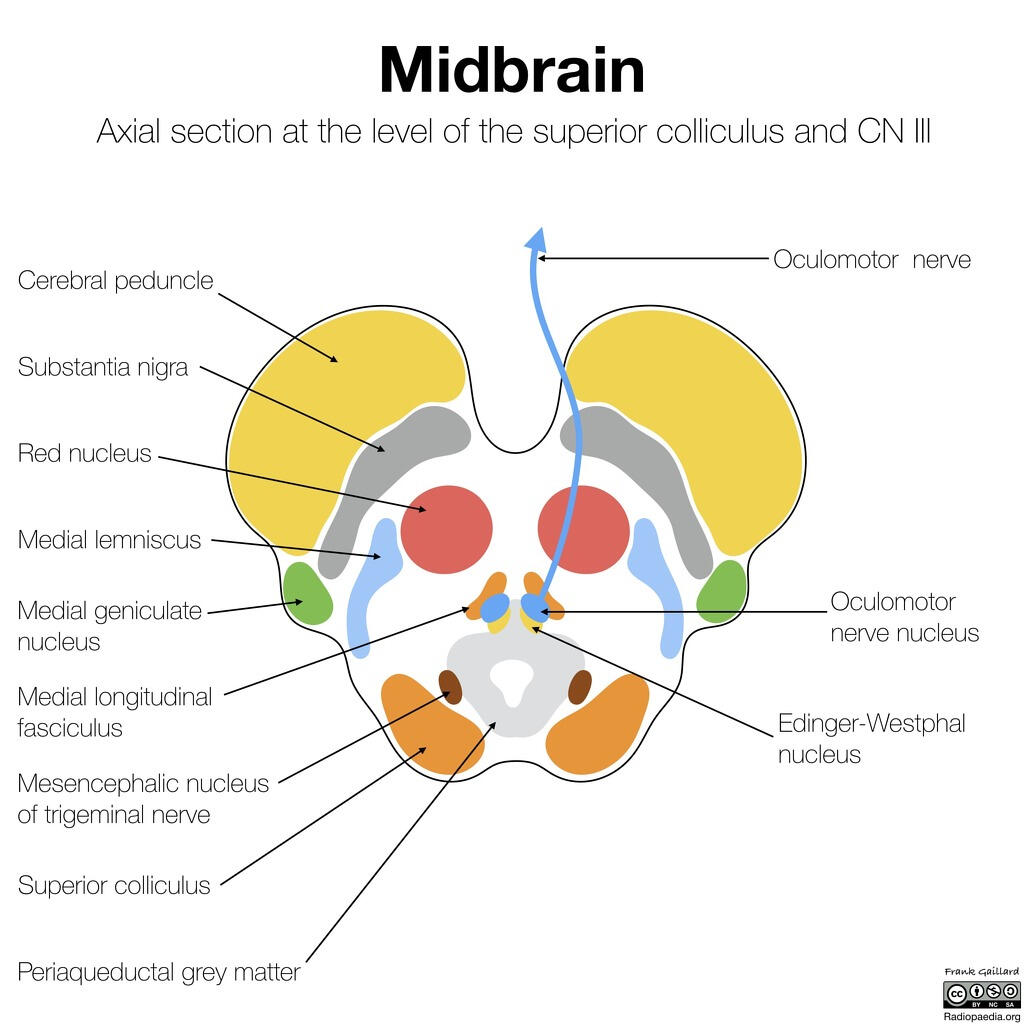

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia - inability to adduct one eye due to lesion in MLF but with compensatory abduction Video Example

Transverse myelitis - defined sensory level loss, weakness in upper or lower extremities, autonomic dysfunction (e.g. bladder/bowel or respiratory)

Brainstem syndrome presenting with ataxia, vertigo, or dysarthria

Upper cervical cord lesions can have L'hermitte's sign (electric-like shock radiating down the back with flexion of the neck)

MS relapse usually lasts for a minimum of 24 hours without an alternative explanation. However, patients with MS can also have fluctuations in their symptoms due to concurrent infection (e.g. UTI), fevers, or heat which represent pseudo-relapses and need additional work-up

Common MS Mimics

| Inflammatory | Infectious | Neoplastic | Vascular | Metabolic/Toxic | Genetic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOG ADEM | - | Lymphoma | Vasculitis | Osmotic myelinolysis | CADASIL |

| Neurosarcoid | Syphilis | Brain metastases | Susac’s syndrome | Carbon monoxide leukoencephalopathy | Adrenoleukodyrstrophy |

| Behcet’s | Lyme | – | Virchow-Robins spaces | Vitamin B12 deficiency | MELAS |

| Sjogren’s | HIV | – | CADASIL | PRES | Fabry’s disease |

| SLE | PML | – | – | Heroin inhalation | Familial hyperlipidemia |

| Tumefactive MS | TB | – | – | Marchiafava-Bignami disease | Phenylketonuria |

| Balo concentric rings | – | – | – | – | – |

Algorithm

Click image to enlarge

Investigations

Work-up for diagnosis

An MS diagnosis is based on clinical history and MRI. Additional investigations do NOT always need to be performed

MRI brain and spine with GAD - (important to include GAD to look for enhancing, active lesions)

Lumbar puncture - send for oligoclonobands (CSF and serum)

Bloodwork - Consider serum NMO/MOG in appropriate context

Consideration of immunotherapy

CBC, lytes, extended lytes, Cr, LFTs, TSH

Hep B core antibody, Hep C

TB skin test prior to certain immunotherapies

Strongyloides testing if from endemic region

Relapse vs pseudo-relapse

Chest x-ray, urinalysis and urine culture, blood cultures x2

Treatment

The treatment section will focus specifically on treating patients who are admitted to hospital for an exacerbation of their MS symptoms.

Glucocorticosteroids (1st line)

Indications: Acute disabling MS relapse

Dosage & Duration: IV methylprednisolone 1g OR PO prednisone 1250mg for 3-5 days

Contraindication: Sepsis or severe infection

Precautions: Administer in AM to minimize nighttime insomnia

Adverse Effects of Glucocorticosteroids

Short-term: GI upset, psychiatric symptoms (insomnia, depression, mania, hallucinations), hyperglycemia, susceptibility to infections

Long-term: Hypertension, weight gain, osteoporosis and avascular necrosis of the hip (rare)

Plasma Exchange (2nd line)

No clear evidence for PLEX in people with MS, though sometimes used in an off-label fashion if severe relapse with poor recovery

Indications: Acute, severe MS relapses poorly responsive to glucocorticosteroids

Dosage & Duration: 1 PV exchange x7 over 14 days

Contraindications: Prior anaphylactic reaction

Precautions: Central line insertion may be required

Adverse Effects of Plasma Exchange

Mild: Citrate toxicity, hypotension, fever/chills/rigor, urticaria, pruritis

Severe: Arrythmia, thromboembolism, pulmonary edema, seizures, coagulopathy, angioedema, bronchospasm, anaphylaxis

Indications: Acute, severe MS relapses poorly responsive to glucocorticosteroids or PLEX; MS relapses in pregnancy

Dosage & Duration: 2 g/kg over 2-5 days

Contraindication: Prior anaphylactic reaction

Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disease (NMOSD)

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Reviewed by Dr. Alex Muccilli

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

NMOSD is an inflammatory disease of CNS characterized by episodes of optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, and other focal neurological symptoms

AQP4 (Aquaporin-4) IgG is the most common antibody found in patients with NMOSD (80% of cases)

Consider MOG (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) IgG in seronegative patients

Less common in predominantly Caucasian countries

Diagnostic Criteria of NMO with (+) AQP4 IgG:

One core clinical feature: optic neuritis, acute myelitis, area postrema syndrome, other brainstem syndrome, symptomatic narcolepsy or acute diencephalic syndrome with with MRI lesion(s), symptomatic cerebral syndrome with MRI lesion(s)

No better explanation

Diagnostic Criteria of NMO without AQP4 IgG:

2+ core clinical features including 1 of optic neuritis, acute myelitis, or area postrema syndrome

Meets MRI requirements for clinical features (see below)

Dissemination in space met with two or more different core clinical characteristics

No better explanation for the clinical syndrome

Negative testing for AQP4 IgG (ideally with cell-based testing)

MRI criteria for seronegative NMOSD

Optic neuritis with either normal MRI or optic nerve lesion (T2/FLAIR or T1-GAD) involving more than half of the optic nerve or chiasm

Acute myelitis with MRI cord lesions extending over 3 + continuous segments (or atrophy in patients with remote history of myelitis)

Acute area postrema syndrome: Dorsal medulla lesion

Acute brainstem syndrome: Periependymal brainstem lesions

| MS | NMO | MOG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optic neuritis | Variable severity (rarely severe) with 2/3 affecting posterior optic nerve, good recovery | Can present as bilateral simultaneous optic neuritis; posterior nerve involvement and may involve optic chiasm; uncommon to have disc edema; more severe with poor prognosis for visual recovery (; can have recurrent attacks | Can present as bilateral simultaneous or unilateral optic neuritis; longitudinal, anterior optic neuritis; disc edema and perineural gadolinium enhancement; better visual outcome than NMO |

| Transverse myelitis | Preference for posterior and lateral cord; lesions will be less than 3 vertebral bodies in length | Lesion extends 3+ vertebral segments; preference for central cord but can expand; more than ⅔ of the axial cord will be involved swollen cord; enhancement; often poor prognosis with permanent gait instability | Linear or expansile lesions, preference for conus |

Investigations

Serum anti-aquaporin-4 IgG - greater specificity than in CSF and with cell based assays

Serum MOG antibodies - greater specificity than in CSF

Do not test MOG in all patients with MS; only send off antibodies in appropriate clinical scenarios

MRI brain +/- spine (depending on symptomatology)

Lumbar puncture if indicated to rule out other causes of optic neuritis/transverse myelitis as indicated

Treatment

Acute therapy: pulse steroids, early PLEX if disabling symptoms (see MS section)

Maintenance: MMF, Rituximab, Azathioprine

New agents that can be used: Eculizumab, Satralizumab, Inebilizumab for AQP4+ NMOSD

MOG+ disease may require longterm immunosuppression with agents such as MMF, Azathioprine, Rituximab, or monthly IVIG

Patient Education

Pediatric patients with ADEM have a 10-15% risk of developing or initially presenting with MOG

Many cases of MOG are monophasic

AQP4+ NMO can be paraneoplastic so consider screening for malignancy in elderly individuals

MOG and MS have typically better functional recovery than NMO

Transverse Myelitis

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Definitions

Transverse myelitis: heterogeneous group of disorders with acute to subacute inflammatory spinal cord syndrome

“Complete” cord lesion: relatively symmetric moderate or severe sensory-motor loss. Suggestive of a monophasic disorder (i.e., infectious) or relapsing NMO

“Partial” cord lesion: incomplete or patchy involvement of at least one spinal segment with mild to moderate weakness and asymmetric or dissociated sensory symptoms. More likely secondary to MS with high risk for relapses in the future

Diagnostic Criteria of Transverse Myelitis

Development of sensory, motor, or autonomic dysfunction due to spinal cord etiology

Clearly defined sensory level

MRI-confirmed exclusion of extra-axial compressive etiology

Inflammation within the spinal cord - CSF pleocytosis, elevated IgG index, or gadolinium enhancement

Progression to nadir between 4 hours and 21 days following symptom onset

Differential Diagnosis

| Demyelinating | Infectious | Inflammatory | Neoplastic | Metabolic | Vascular |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | VDRL | Sarcoidosis | CNS lymphoma | Vitamin B12 | Dural AV fistula |

| NMO | Viral (WNV, Polio, HSV2, EBV, CMV) | SLE | Ependymoma | Vitamin E | - |

| MOGAD | TB | Sjogren’s | Astrocytoma | Copper | - |

| ADEM | Lyme | Scleroderma | Paraneoplastic syndrome (anti-Hu, anti-CRMP-5) | - | - |

| - | HIV | Behcet’s | Primary intramedullary tumor | - | - |

| - | HTLV-1 | - | - | - | - |

Clinical Features

Bowel/bladder dysfunction - constipation, urinary retention, urinary/fecal incontinence

Weakness - upper and/or lower limb involvement depending on spinal level

Hypotonia in affected limbs

Numbness, paraesthesias - upper and/or lower limb involvement depending on spinal level

Pain or tightness - often occurring around stomach or chest

+/- Lhermitte sign

Paroxysmal tonic spasms

Investigations

CT lumbar spine if bowel/bladder symptoms - first rule out cauda equina and indication for surgery!

MRI spine with contrast (level depends on limb involvement)

Serum NMOSD antibodies (see NMOSD section)

LP including infectious work-up

Rheumatological work-up: ANA, anti-dsDNA, ENA, RF, ANCA, C3/C4, APLA

HIV, VDRL, Lyme serology

Vitamin B12, vitamin E

Serum copper

Treatment

Solumedrol 1g IV daily x5 days then maintenance Prednisone 1 mg/kg with slow taper

IVIG 2 g/kg IV over 2 days if no response to steroids

PLEX

Prophylaxis while on high dose steroids: calcium, vitamin D, PPI, PJP prophylaxis

Management of comorbid symptoms (i.e., neuropathic pain, bowel regimen, spasticity, spasms)

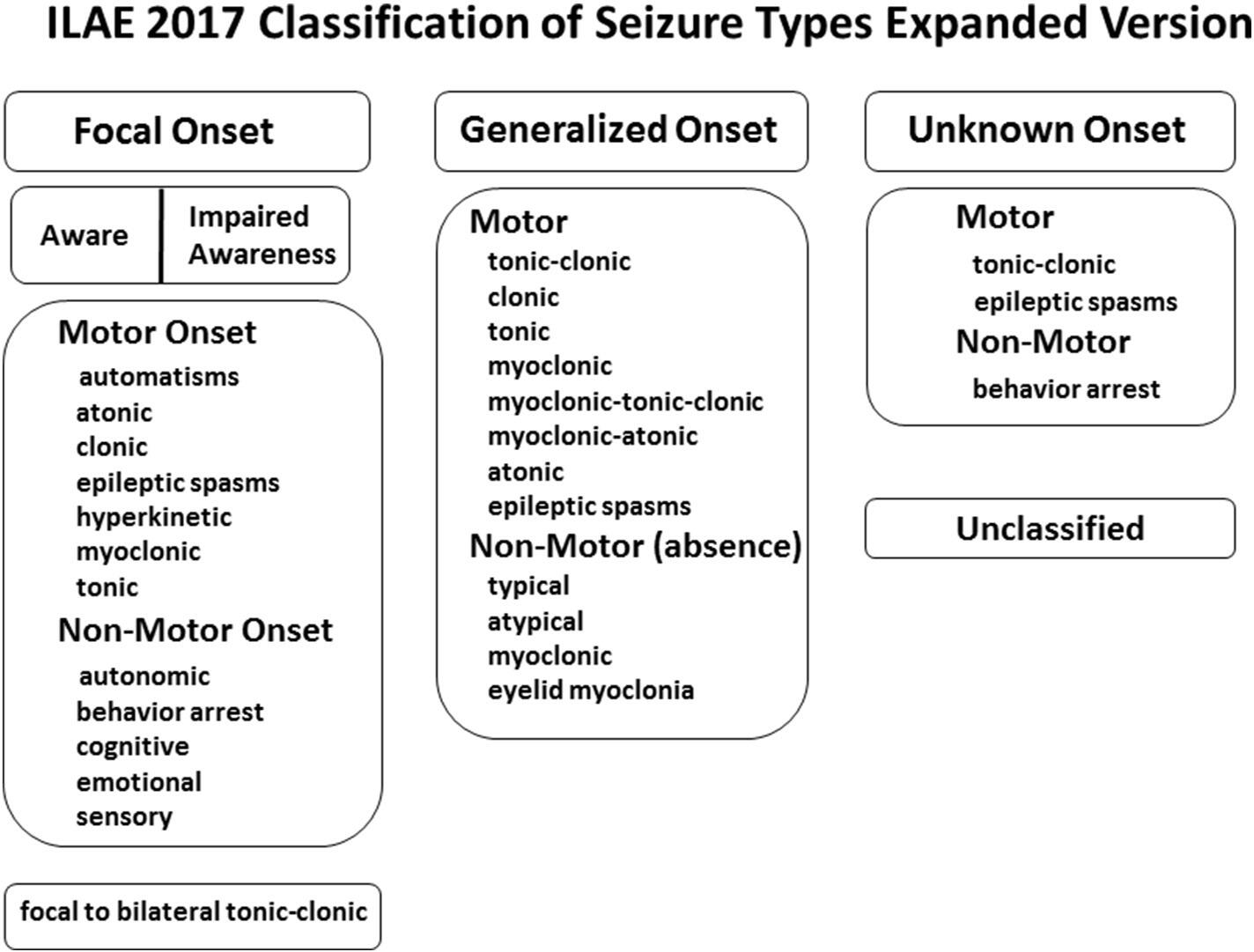

Seizure

Seizure

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Reviewed by Dr. Jerry Chen and Dr. Matthew Burke

Definition

Seizure: A transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms (e.g. sensory, motor, speech, consciousness) due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain

Epilepsy: disorder of the brain with an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition; in a patient who has any of the following:

1) at least 2 unprovoked seizures occurring >24 hours apart;

2) one unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures (similar to the general recurrence risk after two unprovoked seizures (at least 60%) occurring over the next 10 years (e.g. abnormal imaging with a potential seizure focus or EEG with epileptiform activity);

3) diagnosis of epilepsy syndrome (e.g. West, Dravet, Lennox-Gastaut)

Provoked seizure: occur with an identifiable proximate cause (metabolic, toxic, structural, infectious, inflammatory) and are not expected to recur in the absence of that particular cause/trigger (e.g., hypoglycemia, alcohol withdrawal, etc.)

Unprovoked seizure: occur without an identifiable cause or in the context of a remote symptomatic cause (i.e., pre-existing brain lesions, such as a remote stroke). Recurrent unprovoked seizures are more likely to be associated epilepsy

Focal onset (“partial”) seizure: abnormal synchronous neuronal activity originating from one location (within limited to one hemisphere) of the brain, more concerning to be associated with elevated future recurrence risk

Generalized onset seizure: abnormal synchronous neuronal activity arising within and rapidly engaging bilaterally distributed networks

Click image to enlarge

Differential Diagnosis

Stroke/TIA

Syncope: cardiac arrhythmia, orthostatic syncope, vasovagal syncope

Migraine

Encephalopathy: drug-induced, metabolic disturbance

Psychiatric: anxiety/panic attack, PNES

| TIA | Seizure | Migraine Aura | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etiology | Vascular risk factors (e.g. CAD, atherosclerosis) | Trauma, brain lesions (e.g. previous strokes, tumors) | Migraines |

| Cardiovascular manifestations | Frequent | N/A | N/A |

| Neurological manifestations* | Negative symptoms (deficits - weakness, vision loss) | Positive symptoms but can have negative symptoms post-ictal (Todd's Paresis) | Positive symptoms (visual more common), headaches |

| Symptom onset | Sudden | Less than 2 minutes with progression | More than 10 minutes with progression |

| Duration | 5-10 minutes | Less than 5 minutes | More than 20 minutes |

Psychogenic Non-epileptiform seizures (PNES)

Involuntary events in response to internal or external triggers that have similar features to those seen in epileptic seizures, but without corresponding electrophysiological features (i.e., epileptiform discharges)

Patients with epilepsy can also have PNES

Associated with adverse events and trauma

Triggers for PNES may include positional change, physical exertion, emotional/stressful situations, dehydration, or heat

Treatment may involve education and support (see Functional Neurological Disorders section)

| PNES | Epileptic Seizure | |

|---|---|---|

| Preceding aura | Can be variable with shorter duration over time due to dissociation | Sensory, experiential (e.g., déjà vu, jamais vu), autonomic aura |

| Onset of myoclonus | Follows loss of consciousness, occurs with situational associations and often has preserved awareness | Immediate |

| Eye deviation | Upward, often with closed eyes and resistance to eyelid opening | Lateral, with eyes open |

| Myoclonus rhythm | Arrhythmic jerks | Rhythmic jerks |

| Myoclonus pattern | Multifocal jerks briefly involving bilateral proximal and distal muscles; may see pelvic jerking | Unilateral or asymmetric jerks, may exhibit neuroanatomic evolution or GTC behaviour |

| Post-ictal presentation | Fatigue but no confusion, with relatively rapid recovery to baseline | Confusion, +/- Todd’s paresis (hemiparesis) |

Risk factors

Traumatic brain injury

Abnormalities in childhood development and birth history

Febrile seizures

Meningitis and/or untreated meningitis

Intracranial structural lesion: (gliosis, encephalomalacia, mass lesion, developmental malformations, cavernomas)

Previous seizure/epilepsy history

Family history

Neurodegenerative disorders

Seizure triggers

Sleep deprivation

Substance use/withdrawal

Infection

Trauma

Menstruation and ovulation

Non-adherence to treatment

Metabolic abnormalities: hypoglycemia, hyponatremia >hypernatremia, hypocalcemia > hypercalcemia, hypomagnesium

Clinical Features

Preceding aura: somatosensory, experiential (i.e., deja vu, jamais vu, epigastric rising sensation), motor, speech/language, autonomic, olfactory/gustatory, and/or visual perceptual disturbance experienced prior to the seizure with positive phenomenology

Event: level of awareness, circumstances leading up to the event (i.e., sleeping, awake), duration, movements (i.e., facial movements, head deviation, eye movements and deviation, rhythmic vs. arrhythmic limb movements, tonic clonic, posturing), urinary/fecal incontinence, tongue biting

Post-ictal period: confusion, drowsiness/altered level of consciousness, Todd’s paresis (hemiparesis), duration to return to baseline; important to complete neurological examination following event and assess for lateralizing signs

Investigations

Stat CT head to rule out acute intracranial abnormality (i.e., hemorrhage, stroke, mass lesion)

CBC

Lytes, extended lytes (Mg, Ca, PO4), creatinine

Blood glucose

CK

Prolactin (When considering PNES, should be drawn within 10-20 minutes, should be ~2x versus baseline)

Liver enzymes

Toxicology screen if indicated

Blood, urine, CSF cultures if indicated

MRI brain with contrast (seizure protocol) when clinically stable: may see some T2/FLAIR hyperintensity, diffusion restriction (ADC drop >10% is associated with permanent damage)

EEG

AED levels if prescribed to patient

LP with cell count and differential, protein, glucose, bacterial/viral/fungal cultures, cytology/flow cytometry, autoimmune/paraneoplastic panels as indicated

Serum autoimmune/paraneoplastic panels if indicated

Autoimmune work-up: ANA, anti-dsDNA, ENA, RF, C3/C4, cryoglobulins as indicated

If there is suspicion for PNES - prolonged video EEG or EMU is helpful for the diagnosis

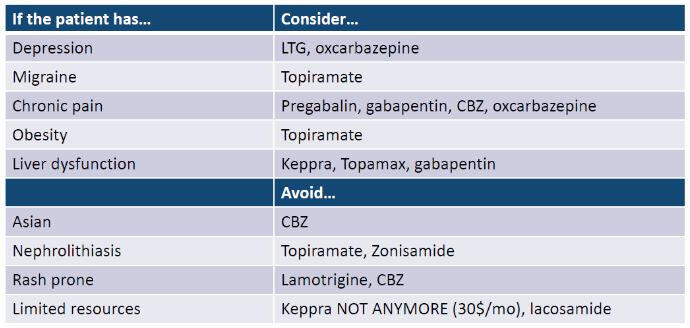

Treatment

ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) and consultation of ICU if the patient may require intubation with prolonged seizure

First-line Benzodiazepines - Midazolam 10mg IM x1 (if patient is >40kg) or Lorazepam 2mg IV q2min (max 8mg)

AED load after acute management if indicated

Patients with a single provoked seizure do not typically require maintenance AED

Maintenance AED: predominantly used if unprovoked seizure with high risk of recurrence or multiple unprovoked seizures or abnormal EEG/MRI or nocturnal seizures

If suspicious of infectious cause, antimicrobials based on suspected organism/etiology should be initiated after the collection of cultures (if possible)

Correction of metabolic abnormalities

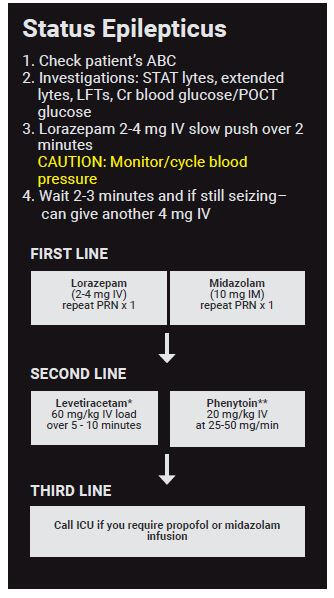

For Pocket Card Algorithm in Status Epilepticus, see Figure 1 in this article: The Efficacy and Use of a Pocket Card Algorithm in Status Epilepticus Treatment

| AED | Load Dose and Rate | Maintenance Dose | Clearance | Side-effects for Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenytoin | 20 mg/kg IV at a rate no faster than 50 mg/min | Start at 300mg p.o. Daily (up to 400mg BID) | Hepatic | Cardiac side-effects (hypotension, QTc prolongation), avoid if possible in patients with hepatic dysfunction |

| Keppra | 40-60 mg/kg IV (max 4500mg) over 5-10 min | Start at 500mg p.o. BID (up to 1500mg BID) | Renal | Avoid if possible in patients with anxiety/depression or renal dysfunction |

| VPA | 20-40 mg/kg IV (max 3000mg) over 20 min | Start at 500mg p.o. BID (up to 750mg BID) | Hepatic | May affect platelet function even without thrombocytopenia, Avoid if possible in patients with hepatic dysfunction |

| Lacosamide | 200-400mg IV | Start at 100mg IV/p.o. BID (up to 200mg BID) | Renal more than hepatic | Cardiac side-effects (PR interval prolongation, heart block, bradycardia), Avoid in patients with type 2 or 3 heart block, sick sinus syndrome |

Click image to enlarge

[Source: Dr. Arina Bingeliene's Emergency Lecture 2020]

In choosing a long-term AED, consider the following:

Seizure type (focal vs. generalized onset, specific seizure syndrome)

Comorbidities

Side effects and tolerance

Dosing frequency

Drug coverage/affordability

Teratogenic AEDs to avoid in pregnancy:

VPA

Carbamazepine

Topiramate

Phenytoin

Phenobarbital

OCP efficacy is reduced by:

High Topiramate levels

Enzyme inducers: Phenytoin, Carbamazepine

Phenobarbital, primidone, oxcarbazepine

Patient Education

Driving: reporting to MTO is a mandatory obligation in Ontario and instruct the patient not to drive until driving privileges are reinstated by the MTO

Precautions to counsel patients surrounding baths alone, swimming alone, heights/dangerous activities (e.g. climbing ladders)

Status Epilepticus

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Reviewed by Dr. Alex Muccilli

Definition

A single seizure lasting more than 5 minutes or multiple seizures with incomplete recovery of level of consciousness to baseline between the seizures

May present as generalized tonic clonic (GTC) seizures or non-convulsive seizures

Defined by 2 time-points: T1 (time beyond which seizures will likely prolong >5 minutes GTC) and T2 (GTC 30 minutes with higher risk for long-term consequences)

Mortality is 20% - most important determinant of mortality is underlying cause

Evidence supporting early treatment of seizures stems from studies showing increasing pharmaco-resistance (especially to benzos) and neuronal injury with longer seizure durations

Causes of status epilepticus

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Serotonin Syndrome

Substance use/withdrawal

Autoimmune encephalitis - suspect if no response to AEDs

Clinical Features

GTC seizure with head and gaze deviation, +/- urinary/fecal incontinence

Non-convulsive seizure - nystagmus, sustained eye deviation, facial/periorbital twitching, abnormalities in vital signs

Post-ictal phenomenon - confusion/agitation, dysarthria/aphasia, altered level of consciousness, Todd’s paresis (unilateral hemiparesis)

Investigations

Stat CT head to rule out acute intracranial abnormality (i.e., hemorrhage, stroke, mass lesion)

CBC

Lytes, extended lytes (Mg, Ca, PO4), creatinine

Blood glucose

Liver enzymes

Toxicology screen if indicated

Blood, urine, CSF cultures if indicated

MRI brain with contrast (seizure protocol) when clinically stable: may see some T2/FLAIR hyperintensity, diffusion restriction (involving cortex, hippocampi/mesial temporal lobes, thalamus, and cerebellum)

EEG

AED levels if prescribed to patient

LP with cell count and differential, protein, glucose, bacterial/viral/fungal cultures, cytology/flow cytometry, oligoclonal bands/IgG index, autoimmune/paraneoplastic panels as indicated

Serum autoimmune/paraneoplastic panels if indicated (see requistions)

Treatment

ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) and consultation of ICU as the patient may require intubation with prolonged seizure

First-line Benzodiazepines - Midazolam 10mg IM x1 (if patient is >40kg) or Lorazepam 2mg IV q2min (max 8mg)

AED load after acute management

| AEDS | Dose and Rate | Side-effects for Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Phenytoin | 20 mg/kg IV at a rate no faster than 50 mg/min | Cardiac side-effects (hypotension, QTc prolongation), Purple Glove Syndrome (Extensive skin necrosis and limb ischemia), Avoid if possible in patients with hepatic dysfunction |

| Keppra | 40-60 mg/kg IV (max 4500mg) over 5-10 min | Avoid if possible in patients with anxiety/depression or renal dysfunction or dose accordingly |

| VPA | 20-40 mg/kg IV (max 3000mg) over 20 min | May affect platelet function even without thrombocytopenia, hyperammonemia, pancreatitis, Avoid if possible in patients with hepatic dysfunction |

| Lacosamide | 200-400mg IV bolus then 100mg IV BID | Cardiac side-effects (PR interval prolongation, heart block, bradycardia), Avoid in patients with type 2 or 3 heart block, sick sinus syndrome |

* Max dose of Levetiracetam is 4.5 g for status epilepticus

** In an average-size (70 kg) individual, consider 1500 mg load of

phenytoin if unable to obtain weight quickly

Click image to enlarge

Consider giving thiamine 500 mg IV followed by 50 ml of D50

Intubated patients may require burst suppression (target 40-60%) and ICU monitoring with titration of sedatives including propofol and barbiturates

If suspicious of infectious cause, antimicrobials based on suspected organism/etiology should be initiated after the collection of cultures (if possible)

Correction of metabolic abnormalities

* Max dose of Levetiracetam is 4.5 g for status epilepticus

** In an average-size (70 kg) individual, consider 1500 mg load of

phenytoin if unable to obtain weight quickly

Patient Education

For patients with known seizure disorders, compliance to AEDs is important to reduce risk of status epilepticus

Movement disorders

Parkinson's Disease (PD)

By Dr. Priti Gros

Reviewed by Dr. Emily Swinkin

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Second most common neurodegenerative disorder following Alzheimer's disease

Due to dopamine deficiency secondary to degradation of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra

Can be genetic (10%) or idiopathic (90%)

Average age of onset in 60’s

Pathologically characterized as an alpha synuclein proteinopathy with presence of Lewy bodies

Clinical Features

Cardinal features of Parkinsonism are: 4-6 Hz Rest tremor, Rigidity, Akinesia/Bradykinesia, and Postural instability not due to visual, vestibular, or cerebellar or proprioceptive dysfunction (TRAP)

Non-motor features of PD: Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep disorders, anosmia, autonomic dysfunction (constipation, orthostatic hypotension), mood changes, cognitive changes

Constipation, REM sleep disorders, and anosmia can precede motor symptoms of PD by over a decade

At present there are no confirmatory diagnostic tests for PD, it is a clinical diagnosis

Many diseases have Parkinsonism features - important to distinguish from PD as they often do not respond to levodopa. Examples include the following:

Drug induced: Antipsychotic use (especially first generation like haloperidol) and dopamine antagonists (e.g. metoclopramide) - can often have tardive dyskinesia and akathsias

Toxins: Manganese, MPTP

Vascular parkinsonism: concomitant vascular risk factors, may be more symmetric and have lower body predominance

Parkinson’s Plus Syndromes (see below)

| Etiology | PSP | MSA | CBS | DLB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset | 60’s | 50’s | 60’s | 50-80’s |

| Features | Difficulties with vertical gaze, falls, axial rigidity | Autonomic dysfunction, cerebellar signs, upper motor neuron signs | Alien limb, apraxia, myoclonus, cortical signs and cognitive impairment | Cognitive changes progressing to dementia with visual hallucinations onset BEFORE or shortly after parkinsonism |

| Neuroimaging | Humming bird and Mickey Mouse sign | Hot cross bun sign | Asymmetrical parietal/basal ganglia atrophy | N/A |

Diagnosis

UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank Criteria:

Step 1: Diagnosis of parkinsonism requires bradykinesia and one of the following features:

Rigidity

4-6 Hz rest tremor

Postural instability “not caused by primary, visual, vestibular, cerebellar or proprioceptive dysfunction

Step 2: Exclusion of “red flags”. One or more could suggest another diagnosis (e.g. Parkinson’s Plus Syndromes)

History of repeated strokes with stepwise progression of parkinsonism

History of repeated injury

History of definitive encephalitis

Neuroleptic treatment at onset of symptoms

MPTP exposure

Negative response to large doses of levodopa

>1 relative affected (this criteria is usually no longer applied)

Sustained remission

Strictly unilateral features after 3 years

Early severe autonomic involvement

Early severe dementia with disturbances of memory, language and praxis

Oculogyric crises

Supranuclear gaze palsy

Babinski sign

Cerebellar signs

Presence of cerebral tumor or communicating hydrocephalus on CT or MRI

Step 3: Supportive features for PD. 3 or more are required for diagnosis of definite PD:

Unilateral onset

Rest tremor

Progressive disorder

Persistent asymmetry affecting the side of onset most

Excellent response (70-100%) to levodopa

Severe levodopa-induced chorea

Levodopa response for 5 years or more

Clinical course of 10 years or more

Physical Exam

Key exam maneuvers and features in Parkinson’s Disease or Parkinson’s Plus Syndromes

Inspection: Decreased facial expression (hypomimia), softer voice (hypophonia), decreased blink rate

Eye movements: Difficulties with extraocular eye movements (e.g. PSP - slowed or impaired vertical saccades), hypometric saccades (Can be tested with OKN strips, in PSP - decreased vertical saccades)

Tremor: Parkinson’s tremor typically occurs at rest and is asymmetrical, but can re-emerge with sustained posture, often described to have a “pill-rolling” quality and can worsen with distraction (“Count months of the years backwards”)

Bradykinesia: Finger tapping, hand open-close, supination-pronation, foot and heel tapping will demonstrate not just slowness but decrement in amplitude or freezing of movements

Tone: Testing for both appendicular rigidity (usually Parkinson’s Disease) and axial rigidity (often seen in PSP)

Gait: Slow, shuffling gait with often stooped posture. Arm swing can be diminished with emergence of tremor. Difficulty with turns, requiring multiple steps to move (en-bloc turning). Patients can walk slowly but then accelerate with small steps (festination). Advanced PD can demonstrate freezing of gait at times which are overcome by visual stimuli (e.g. stepping over a line)

Postural instability: Pull test to look for retropulsion (will require several >3 steps to regain balance)

Other signs: Micrographia or tremor in writing

Investigations

Atypical symptoms may benefit from MRI brain to rule out Parkinson’s Plus syndromes

Treatment

No disease-modifying therapy, only symptomatic management is available yet (see below):

Symptomatic management of motor PD symptoms

| Class of medications | Levodopa | Dopamine agonists | Monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors (MAO-B) | COMT-inhibitors | Anticholinergic drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medications | Levodopa-Carbidopa (Sinemet) | Pramipexole, Ropinirole, Rotigotine | Selegiline, Rasagiline, Safinamide | Entacapone | Trihexylphenidyl |

| Indications | Usually first line, start at Sinemet 100/25 1 tab TID, must be taken with food and protein can reduce efficacy | Less well tolerated in elderly patients due to confusion but less incidence of fluctuations and dyskinesia | Usually add-on to improve efficacy of levodopa | Usually add-on to improve efficacy of levodopa | Best for tremor predominant but only for younger individuals |

| Side Effects | Nausea, GI upset, daytime somnolence, orthostatic hypotension, oedema and can induce dyskinesia in long-term | Nausea, daytime somnolence, hallucinations, impulse control disorders (pathological gambling, hypersexuality, binge eating). | Theoretical risk of serotonin syndrome if on an SSRI/SNRI | Confusion, hallucination, urine discolorations, diarrhea, and dyskinesias | NOT FOR ELDERY, dry mouth, constipation, somnolence, memory changes |

Treatment of non-motor Parkinson's Disease symptoms (non-exhaustive list)

Depression: Dopamine agonist (Pramipexole), Serotonin reuptake inhibitor (Citalopram, Fluoxetine), Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (Venlafaxine), Tricyclic antidepressant (Desipramine, Nortriptyline),

Psychosis: Atypical antipsychotic (Clozapine, Quetiapine), acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (Rivastigmine)

REM Sleep behaviour disorder: Hormone (Melatonin), Benzodiazepine (Clonazepam)

Constipation : Osmotic laxative (PEG)

Gastrointestinal motility : Peripheral dopamine antagonist (Domperidone)

Orthostatic hypotension: peripheral dopamine antagonist (Domperidone), Mineralocorticoid (Fludrocortisone), Vasopressor (Midodrine)

Essential Tremor

By Dr. Priti Gros

Reviewed by Dr. Emily Swinkin

Epidemiology

Common, can be both familial (about 50% will have a family history although no single causative gene yet identified) or idiopathic

Two peaks of onset at 20s and 60s

Clinical Features

Usually an isolated tremor syndrome of the bilateral upper limb presenting as a posture or kinetic tremor, with or without head tremor or tremor in other locations

Benign, but tremors can become progressively worse which may warrant symptomatic treatment

Tremors may improve with small amounts of alcohol

Diagnostic criteria: Essential Tremor

Isolated tremor syndrome of bilateral upper limb action tremor

At least 3 years’ duration

With or without tremor in other locations (e.g. head, voice or lower limbs)

Absence of other neurological signs, such as dystonia, ataxia, or parkinsonism

Exclusion criteria for ET

Isolated focal tremors (voice, head)

Orthostatic tremor with a frequency > 12 Hz

Task- and position-specific tremors

Sudden onset and step-wise deterioriation

Differential Diagnosis

Enhanced physiological tremor: common bilateral upper limb action tremor (8-12 hz), caused by anxiety, fatigue, hyperthyroidism, other drugs. It is often reversible if the cause of the tremor is removed

Parkinson’s disease and other forms of Parkinsonism: classic parkinsonian tremor is typically a 4-7 Hz rest tremor. It can involve the upper or lower extremities, jaw or tongue. See section on Parkinson’s disease. See section on Parkinson’s disease

Cervical dystonia: common cause of isolated head tremor.

Task- and position-specific tremors: focal tremor that typically occur during a specific task or posture

Primary orthostatic tremor: a generalized high frequency (13-18 hz) isolated tremor syndrome that occurs upon standing up. Often, confirmation of the tremor frequency is done using electromyography

Functional tremor: characterized by distractibility, frequency entrainment or antagonistic muscle coactivation

Investigations

Generally no investigations are needed unless there are atypical findings

Treatment

First line treatments

Propranolol

Initial dose: 60 - 80 mg/day (divided into two or three doses per day, e.g. 40 mg BID) and gradually titrate up to efficacy (may start at lower dose in elderly)

Maintenance dose : 120 to 320 mg/day (Lower dose is better for elderly individuals)

Side Effects: Lightheadedness, bradycardia, fatigue

Contraindications: Patients with heart block/heart failure, asthma, and type 1 diabetes

Primidone

Initial dose: 25 mg/day (at bedtime) and increase by 25 mg every 3-7 days

Maintenance dose : 250 mg - 500 mg/day

Side Effects: Sedation, drowsiness, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, ataxia

Second line treatments

Propranolol + Primidone

Gabapentin 100-300mg p.o. TID (max 1200mg daily)

Topiramate 25mg p.o. daily-BID (max 400mg daily)

Surgical treatments

MRI-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy

Deep brain stimulation to thalamus

Patient Education

The clinical course of ET is typically slow, progressive over years

Younger age of onset usually correlates with slower progression

Myoclonus

By Dr. Caz Zhu

Reviewed by Dr. Emily Swinkin

Definition

Sudden, brief involuntary muscle jerks that occur occur at rest, movement, or provoked by stimuli (e.g. touch, sound)

Positive myoclonus: Caused by abrupt muscle contraction

Negative myoclonus: Caused by loss of tone (e.g. asterixis)

Clinical Features

Cortical myoclonus: Usually affecting the face and hands and with voluntary action. stimulus sensitive and triggered by action or touch, can also be seen in certain epilepsy syndromes

Subcortical/Brainstem myoclonus: Generalized jerks in axial and bilateral proximal extremities, stimulus sensitive to auditory triggers - startle response (e.g. loud clap)

Spinal myoclonus (Propriospinal myoclonus and segmental spinal myoclonus): Usually arrhythmic jerks in the arm/trunk but in propriospinal myoclonus, you can see abdominal myoclonus (torso flexion)

Secondary myoclonus is the most common form of myoclonus - due to an underlying neurological or non-neurological cause → important to differentiate whether onset of myoclonus is acute vs gradual

Diffuse myoclonus is often seen post-anoxic brain injury (associated with poor prognosis) - e.g. Lance-Adams Syndrome

Differential Diagnosis

*This is not an exhaustive list but some of the common causes of myoclonus to consider

| Classification | Common causes |

|---|---|

| Toxic-Metabolic | Hepatic & renal failure, electrolyte abnormality, hyperthyroidism |

| Drug-induced | SSRIs, dopamine agonists, opioids, antibiotics (cephalosporins), benzodiazepine withdrawal |

| **Infectious ** | Herpes Simplex Encephalitis |

| Trauma | Lance-Adams Syndrome (action-induced myoclonus during recovery of anoxic brain injury) , spinal cord injury |

| Neurodegenerative Diseases | CJD, cortico-basal degeneration, other dementias |

| Paraneoplastic | Anti-Ri antibodies (breast and lung cancer) |

| **Epileptic Myoclonus ** | Childhood myoclonic epilepsy (lennox-gastaut syndrome), Progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MERRF) |

| Essential | Purely isolated myoclonus |

| **Physiological ** | Hynagogic myoclonus (falling asleep), hiccups, physiological startle |

Investigations

CBC, lytes, extended lytes, LFTs, TSH

MRI brain in appropriate clinic context to evaluate for anoxic injury, brainstem pathology, neurodegenerative conditions

EEG and EMG may be helpful but generally not required for diagnosis

Treatment

If reversible cause of myoclonus is found (e.g. due to metabolic cause or drug-induced) - need to treat

Symptomatic treatment for myoclonus:

| Cortical | Subcortical | Spinal | Focal peripheral myoclonus (hemifacial spasm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapies | Valproic acid, Clonazepam, and Levetiracetam | Clonazepam | Clonazepam | Botox injections |

Stroke

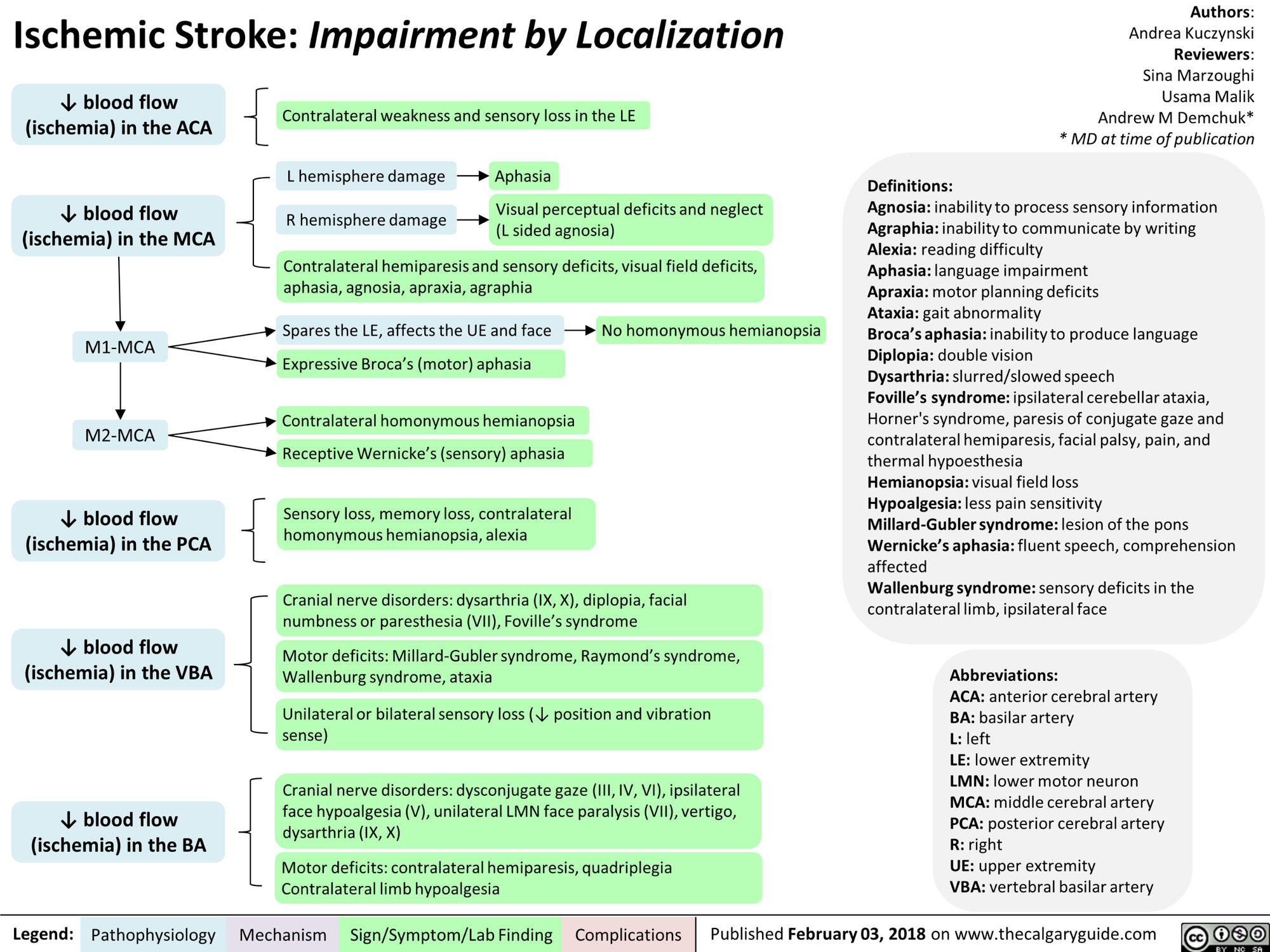

Ischemic Stroke

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Reviewed by Dr. Houman Khosravani

Definitions

Ischemic stroke: hypoperfusion of brain tissue due to thrombus/embolus within the intracranial vasculature

TIA*: transient episode of neurological dysfunction due to focal ischemia without infarction; should see resolution of symptoms without neuroimaging correlate if symptoms resolve within 24hrs and typically do not see neuroimaging correlate if symptoms resolve within 2hrs

High risk TIA: high risk for occurrence of an ischemic stroke within the first 48hrs in a patient with transient unilateral motor and/or speech/language symptoms lasting >5 minutes

Increasingly, there is recognition that TIA is not the best terminology and we expect the field to revolve to potentially remove this term; but for now it remains

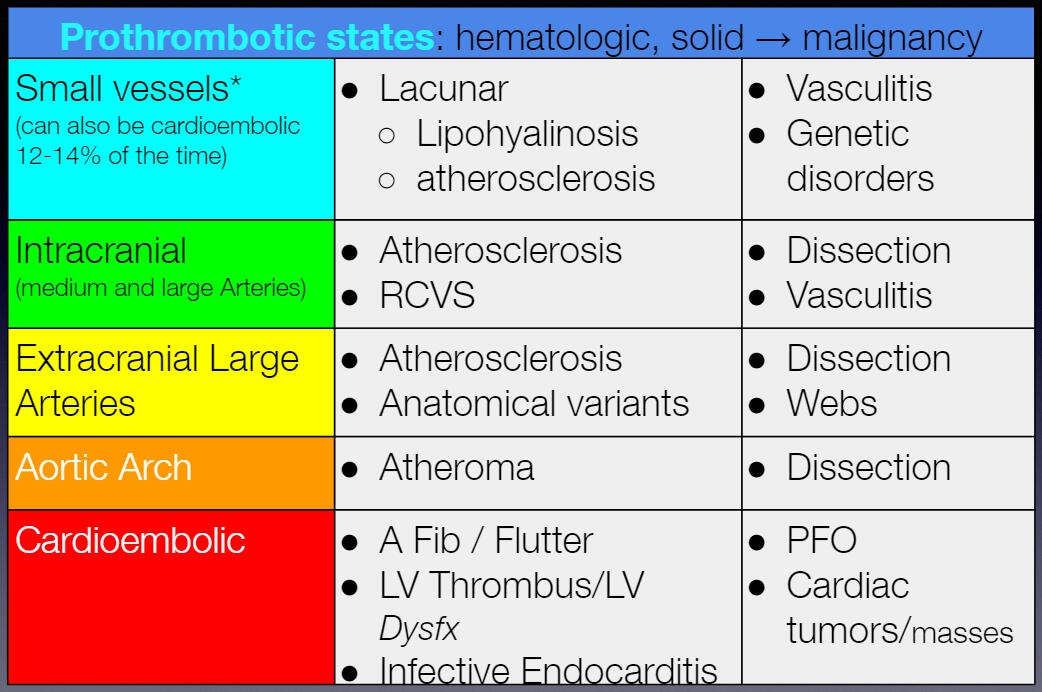

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Cardioembolic - secondary to atrial fibrillation

Large vessel atherosclerosis

Small vessel/lacunar strokes - secondary to HTN

Other (more common in young patients <50) - PFO, carotid/vertebral dissections

Cryptogenic/unknown

Source: Dr. Houman Khosravani

Risk factors

HTN

Dyslipidemia

Diabetes

Smoking

Atrial fibrillation

Cardiac disease/PVD

Obesity/reduced physical activity

EtOH misuse

Pro-thrombotic/hypercoagulable state - OCP/hormone replacement use, SLE, APLA, Factor V Leiden, protein C and/or S deficiency, anti-thrombin III deficiency, malignancy

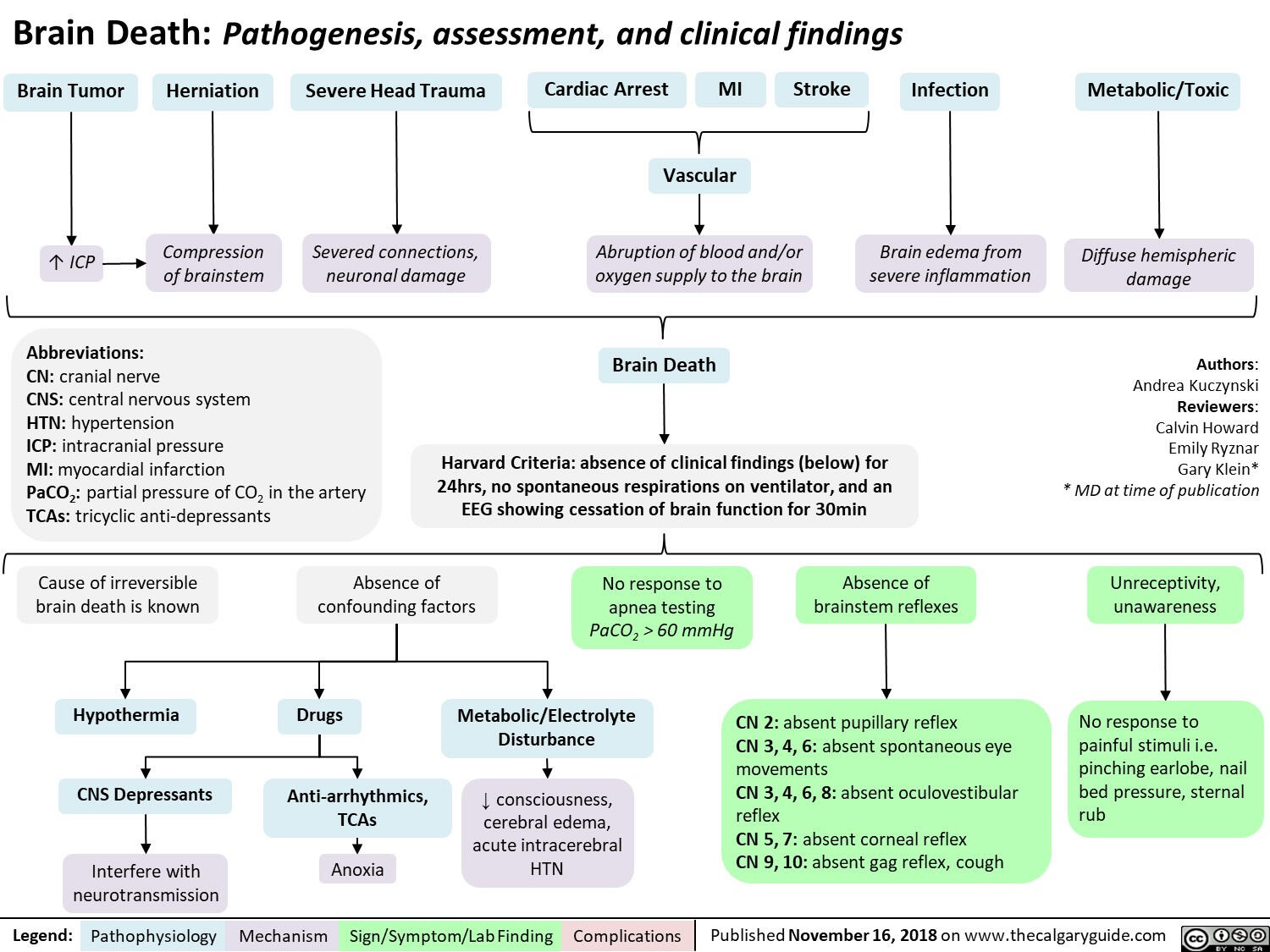

Click image to enlarge

Source: The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease

⊙ CLINICAL PEARL

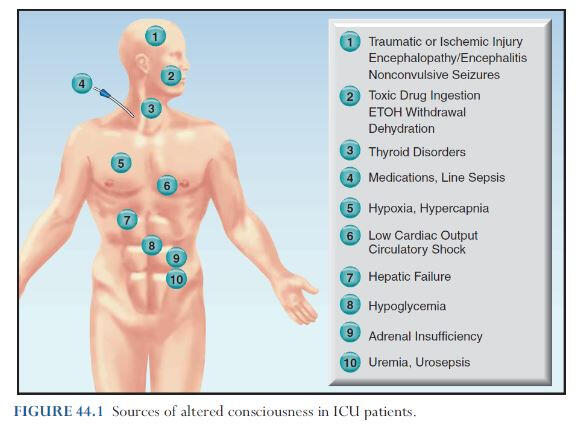

Patients may present with a variety of symptoms including headache, altered mentation, seizure, unilateral and/or brainstem deficits

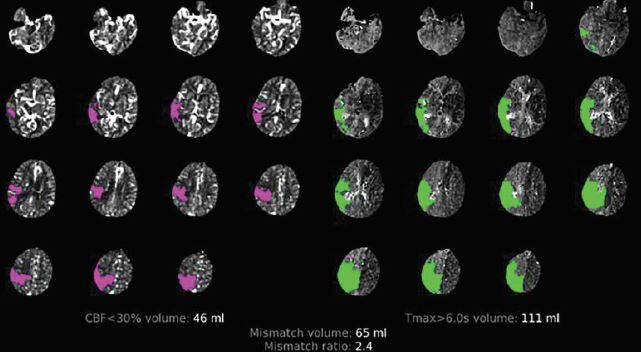

Investigations

Stat CT/CTA/CTP - assess for ischemic changes, hemorrhage, arterial occlusion, perfusion mismatch

NIHSS clinical examination

Vital signs including heart rate and BP

ECG

CBC

Lytes, extended lytes (Mg, Ca, PO4), creatinine

Blood glucose

24 hours after tPA and/or EVT: CT head

MRI brain when clinically stable

Lipid profile

HbA1c

Transthoracic +/- transesophageal echo with bubble study/definity contrast to look for vegetations, intracardiac thrombus, and/or PFO; TEE is for valves/PFO

In appropriate situations, consider cardiac CT for LAA clot

Blood and urine cultures - especially if patient is febrile and has risk factors for endocarditis (i.e., younger age, IVDU

Holter monitor

CT early signs of ischemic stroke:

Hyperdense vessel

Loss of grey-white differentiation

Sulcal effacement

Loss of insular ribbon

Hypoattenuation of deep grey matter nuclei - highly specific for ischemia within 6hrs

Swelling/mass effect

For the ASPECTS score figure see ASPECTS (Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score) Assessment of the Perfusion–Diffusion Mismatch

CT perfusion:

Assess the core and the penumbra (brain at risk)

Core features: increased MTT, markedly decreased CBF and CBV

Penumbra features: increased MTT, moderately reduced CBF, normal/increased CBV

More likely to have favourable outcome with mismatch ratio >/= 1.8, volume >/= 15mL

Click image to enlarge

[Source: Dr. Phavalan Rajendram Emergency Lecture 2020]

Treatment

Assess patient for stability and call for help from the emergency department/ICU as needed

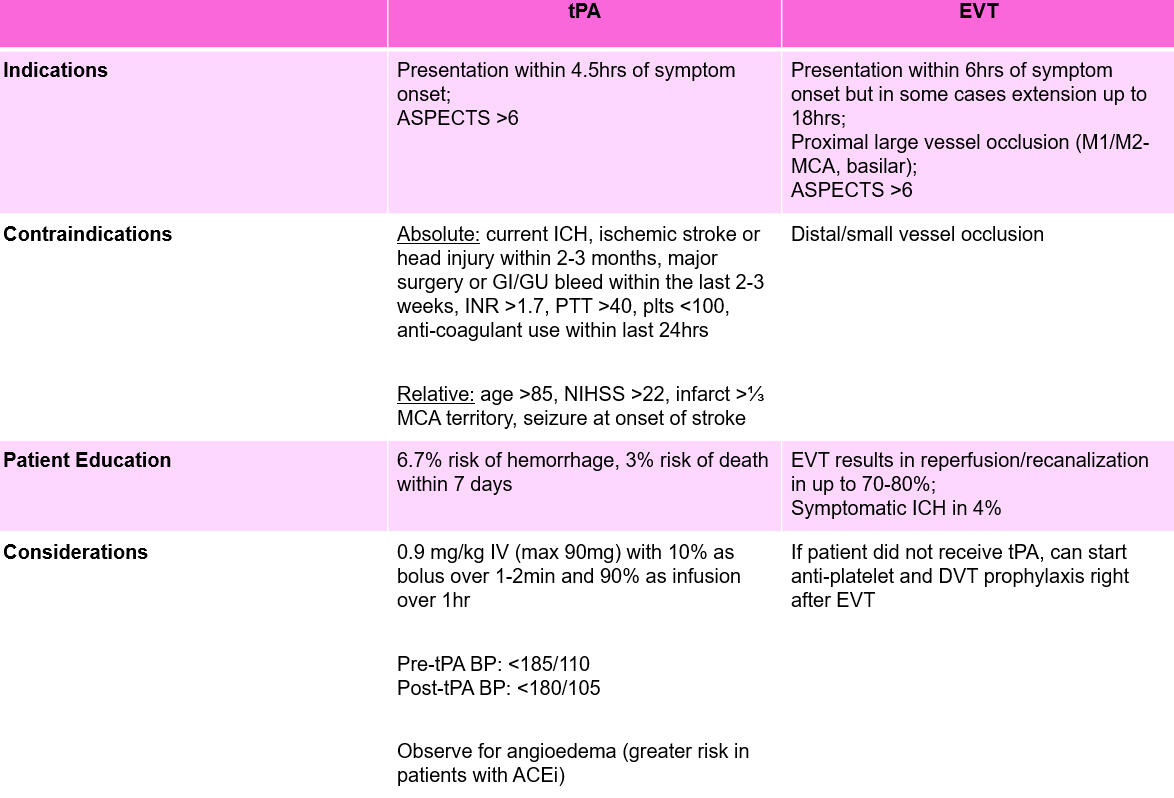

Thrombolysis (TPA/TNK) and/or EVT (see below)

Thrombolysis-angioedema: Solumedrol 125mg IV or Hydrocortisone 200mg IV + Famotidine 20mg IV IV or Diphenhydramine 50mg IV

If clinically stable with stable CT head 24hrs post-intervention (tPA, EVT), can start single anti-platelet and DVT prophylaxis

If NIHSS </= 3 can start dual anti-platelets for 21 days, then monotherapy life-long thereafter (CHANCE, POINT trials)

Starting anti-coagulation post-ischemic stroke (i.e., for AFib): initiation on day 3 (small stroke), 6-7 (medium), or 12-14 (large stroke) but depends on staff and presence of any hemorrhage Reference: Secondary Stroke Prevention Guidelines 7.2

BP: target <140/90 or <130/80 (diabetic patients/small vessel disease)

Dyslipidemia: target LDL <1.8 for those with small vessel disease

Carotid endarterectomy versus stenting in patients with symptomatic large vessel atherosclerosis

Diabetes: target HbA1c <7% (some leniency in patients >80 based on Canadian Diabetes Association)

Must address driving based on residual function as an inpatient!

Lifestyle: cessation of smoking, physical activity, reduced salt intake/DASH diet/Mediterranean diet, reduced EtOH intake

Hemorrhagic Stroke

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Reviewed by Dr. Keithan Sivakumar

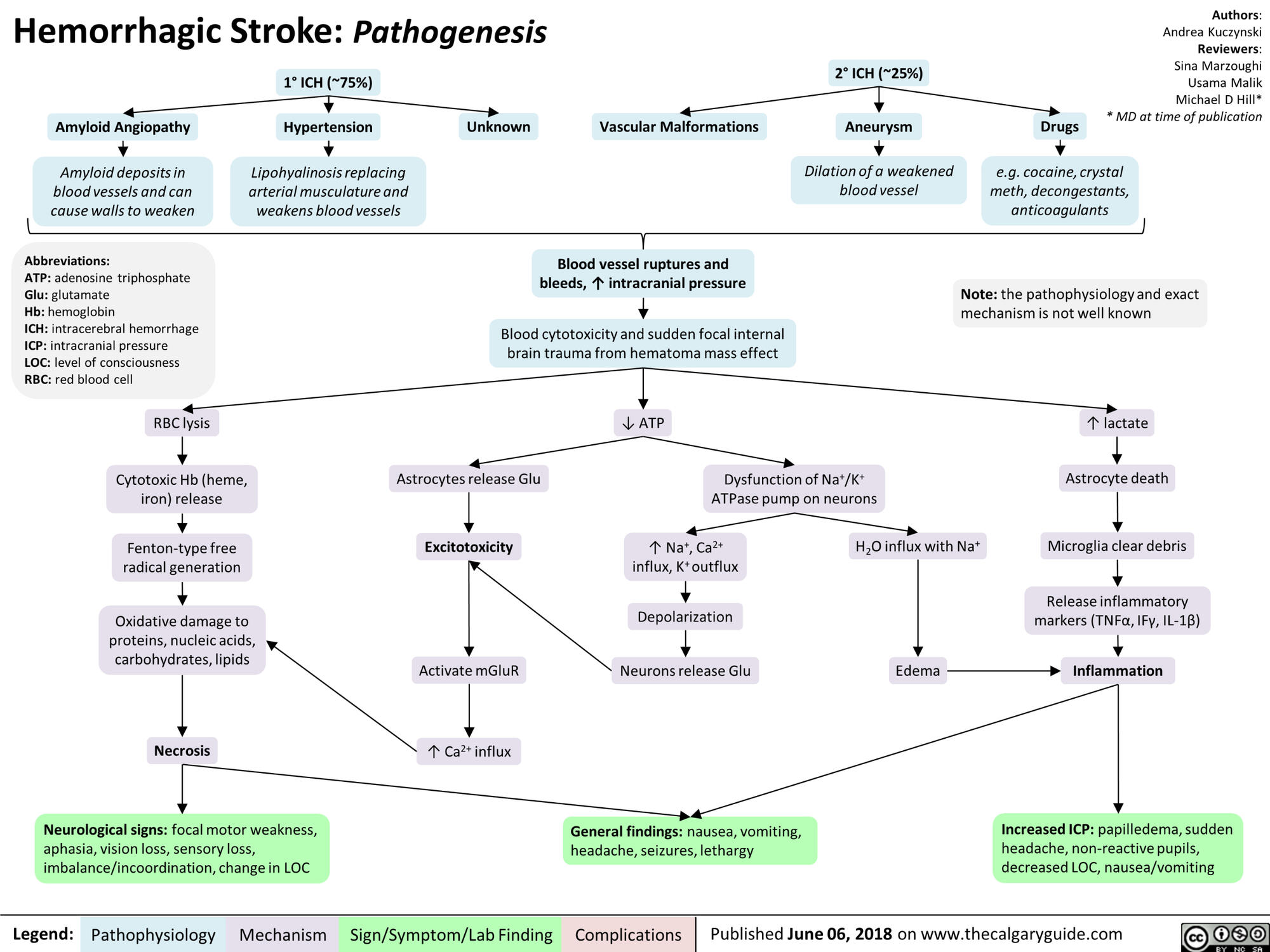

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Etiology characterized based on location - lobar (CAA, ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic transformation), deep (HTN, tumor/metastasis), intraventricular (extension from HTN hemorrhage in basal ganglia, aneurysmal rupture, intraventricular AVM/tumor)

Less common stroke type (10-15%) - more common in individuals with hypertension and older adults (presence of CAA)

Risk factors

HTN

Age - > 65

Trauma & Head Injuries

Vascular anomalies - arterial dissection, CVST, AVM, aneurysmal rupture

Tumors/metastasis

Sympathomimetic drugs (e.g. cocaine, amphetamines)

Smoking

EtOH misuse

Family history

Click image to enlarge

Source: The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease

Clinical Features

Headache - often described as sudden onset & worst headache (thunderclap)

Altered level of consciousness

Nausea/vomiting

Dizziness/vertigo

Focal neurological deficits

Seizure

Investigations

Stat CT/CTA/CTP - assess for ischemic changes, hemorrhage, arterial occlusion, perfusion mismatch

NIHSS clinical examination

ICH score

Vital signs including heart rate and BP

ECG

CBC

Lytes, extended lytes (Mg, Ca, PO4), creatinine

Blood glucose

Blood and urine cultures - especially if patient is febrile and has risk factors for endocarditis (i.e., younger age, IVDU) and subsequent mycotic aneurysms/emboli with hemorrhagic transformation

CT head 6-24 hours after initial presentation

MRI brain when clinically stable with SWI/GRE sequence

Common CT findings in hemorrhage:

Ventricular effacement

Midline shift

Hyperdense blood with surrounding hypodensity (edema)

Spot sign - active bleeding

Treatment

Acute treatment for all ICHs

Acute BP control: SBP <140 (if spot sign present indicating active bleeding) versus SBP <160 (if initial SBP >220 and/or renal dysfunction, absence of active bleeding)

Eventually target BP <140/90 or <130/80 (diabetics)

If patient uses Warfarin, can give Octaplex 1000IU (for patients 50-90kg with INR 1.5-4) and vitamin K 10mg IV push, TXA 1g IV push

Consult Neurosurgery - consideration of EVD and/or decompressive hemicraniectomy if indicated

Avoid secondary brain injury: treat Hb <70, avoid fever, correct coagulopathy

Patients do not require anti-platelets!

Risk factors for poor prognosis: ICH score - older age, initial GCS 3-4, intraventricular hemorrhage, hemorrhage volume >30mL

Stroke in the Young

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Typically considered a “stroke in the young” in an individual <50 years old

Systemic disease associated with prothrombotic state and infarct/hemorrhage: SLE, APLA, vasculitis, Behcet’s, Susac syndrome

| Carotid Dissection | Vertebral Dissection | CVST | Endocarditis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors | Head/neck trauma, connective tissue disease (Marfan’s, Ehlers Danlos, fibromuscular dysplasia), neck manipulation (yoga, chiropractor) | Head/neck trauma, connective tissue disease (Marfan’s, Ehlers Danlos, fibromuscular dysplasia), neck manipulation (yoga, chiropractor) | Prothrombotic conditions, hematological disorders, systemic disease (SLE, IBD), incidental finding in trauma cases | Immunocompromised host, IVDU, mechanical/prosthetic valve, atrial myxoma, intracardiac thrombus, marantic endocarditis |

| Clinical Features | Headache, ipsilateral neck pain, possible ipsilateral Horner’s (rare), retinal/cerebral ischemia, pulsatile tinnitus | Headache, nausea/vomiting, vertigo/dizziness, unilateral pain/weakness | Diffuse, acute onset (thunderclap) headache, diplopia secondary to CN6 palsy, nausea/vomiting, altered level of consciousness | Depends on area of infarction; systemic signs including Osler’s nodes, splinter hemorrhages, etc. |

| Investigations | CTA: crescent sign | CTA: crescent sign, double lumen sign | CT/CTV: delta sign/empty delta sign, subarachnoid hemorrhage, dense cord sign | CT/CTA: may see mycotic aneurysms |

| Treatment | Single anti-platelet (CADISS trial) | Single anti-platelet (CADISS trial) | Anti-coagulation | Treat underlying endocarditis |

Clinical Features

See ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke for full description of focal neurological deficits

Investigations

See ischemic stroke section for basic blood work, neuroimaging, and standard stroke investigations

Autoimmune work-up: ESR/CRP, ANA, anti-dsDNA, ENA, RF, C3/C4, cryoglobulins

Pro-thrombotic/hypercoagulable state work-up: APLA (anti-cardiolipin, B2-glycoprotein-1, lupus anticoagulant), Factor V Leiden, protein C and/or S deficiency, anti-thrombin III deficiency, testicular U/S in males, CT chest/abdo/pelvis for malignancy work-up

Infectious work-up: VDRL, HIV serology

Treatment

Depends on etiology (see table above for examples)

Cognitive Neurology

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

By Dr. Calvin Santiago

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Caused by build-up of CSF

Idiopathic NPH (iNPH): Unknown etiology

Secondary NPH (sNPH): Due to conditions impairing CSF absorption (e.g. SAH, brain tumors)

Clinical Features

Insidious onset of changes starting with gait, then urinary and/or cognitive changes

Initially develops non-specific gait difficulties (slowing of gait, feeling imbalanced) before developing difficulties with initiating of gait (previously known as magnetic gait) or increased falls due to postural instability

May start with increased urinary frequency, than urgency, and finally incontinence

Cognitive impairment includes difficulties in executive dysfunction (e.g. multitasking, judgement)

Neuro-imaging Features

Ventriculomegaly present

DESH (disproprotionately enlarged subarachnoid hydrocephalus)

Crowding present

Transependymal flow present

Significant ischemic white matter changes present

Evans index >0.3

Callosal angle between 40º and 90º

Questions to consider

Are there secondary causes of NPH? (e.g. Head trauma, meningitis, SAH, ICH, tumors)

Does the patient have arthritis, spinal disease, pain/sensory symptoms, or other causes (e.g. poor vision, hearing, parkinsonism) that also explains gait difficulties?

Are there other confounders to diagnosis? (e.g. Sleep apnea, fecal incontinence, headaches, REM sleep disorders, orthostatic hypotension, anosmia)

Was gait difficulty before or after cognitive decline? - Gait onset before or at same time as cognitive changes has a good prognosis of shunting, not true if cognitive decline occurred prior to gait changes

How long have they had cognitive changes and do they have other comorbid cognitive dysfunction? - 2+ years of cognitive decline indicates poor prognosis with shunting

Investigations

UHN NPH protocol developed by Dr. Tang-Wai and Dr. Fasano - for use at UHN but can be used as a reference guide at other sites (i.e. but should not be printed and placed in patient's chart)

Physical exam to assess for orthostatic hypotension, extraocular eye movements, parkinsonism, UMN presence, and peripheral neuropathy

MRI Brain with sagittal FIESTA sequence

Need high clinical suspicion of NPH before proceeding with the NPH assessment

NPH assessment

Pre and post- MOCA with semantic fluency (e.g. animals), and naming (BNT-15)

Pre- video recording of gait (stand up from chair, walk towards camera for at least 10 meters, turn, walk back to chair, repeat)

Large volume lumbar puncture (30-40 cc)

1 hour post-LP - Video record of walk

3 hour post-LP - Video record of walk

** Note: Gait is best performed at a Gait Lab to determine if gait is improved/changed

Treatment

If patient demonstrates improvement of gait post large-volume LP, they should be referred and assessed by Neurosurgery for possible shunt

Patient Education

Unfortunately, prognosis can still be poor without guarantee for improvement post-surgery and there can significant complications including infections and shunt malfunctions post-operatively

VP shunt’s main purpose is improvement in gait and urinary incontinence but NOT cognitive impairment

CREUTZFELD-JAKOB DISEASE

By Dr. Andrea Kuczynski

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

Rapidly progressive dementia due to prion disease (conformational change of proteins)

Sporadic CJD: age 55-70 years, mean 64 years

Variant CJD: mean 26 years, longer duration of symptoms >6 months

Iatrogenic CJD: rare, due to dura mater transplantation

Heidenhain variant CJD: targeting of prions to occipital lobe

Fatal Familial Insomnia: 50's, progressive sleep and autonomic disturbances (hypertension, tachycardia, hyperhidrosis), ataxia

Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheniker: 40-50's, progressive cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus and then with cognitive and UMN symptoms

Clinical Features

Altered level of consciousness/mental status

Psychosis - delusions, hallucinations

Progressive cognitive impairment

Myoclonus

Seizures

Cortical visual disturbances (especially in Heidenhain variant CJD) - disturbed perception of colours or structures, optical distortions, hallucinations

Cerebellar ataxia

Extrapyramidal symptoms

Investigations

MRI brain - diffusion restriction in striatum and cortex (cortical ribboning), pulvinar sign, Hockey stick sign

LP - RT-QuIC assay with elevated 14-3-3 tau

EEG - periodic sharp wave complexes and triphasic components

Differential of cortical ribboning/striatal involvement:

Acute severe hepatic encephalopathy

Autoimmune encephalitis

Hypoglycemic brain injury

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

Mitochondrial disease

Post-ictal state

Extrapontine osmotic demyelination

EBV encephalitis

Treatment

Supportive care

Management of comorbidities and symptoms (i.e., anti-epileptic medication)

Patient and family counseling

Patient Education

Average survival 6-7 months from diagnosis for most cases of CJD, although GSS can be longer (years)

Early involvement of the thalamus is a poor prognostic sign

Neuromuscular & Peripheral Neuropathies

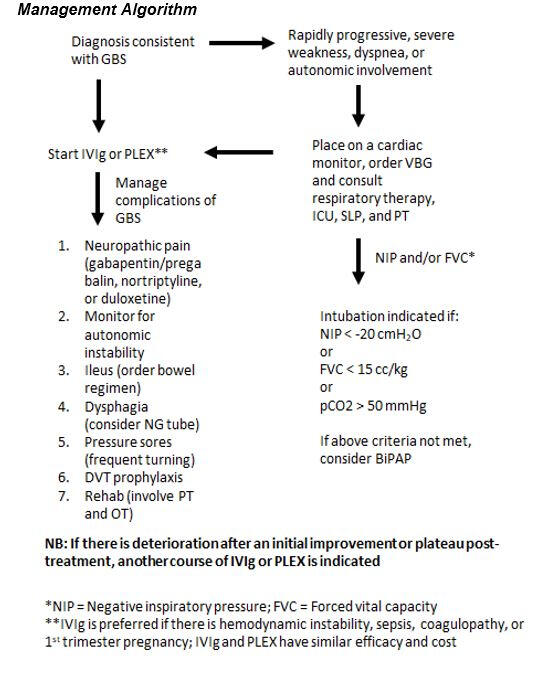

Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS)

By Dr. Elliot Cohen

Reviewed by Dr. David Fam

Pathophysiology and Epidemiology

AIDP - Acute or subacute onset autoimmune demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy - often thought to be preceded by respiratory or GI infection

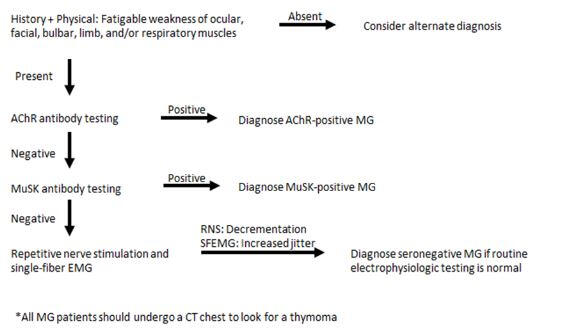

Clinical Features

Numbness/paresthesias and weakness beginning in the legs, progressing proximally, commonly involving the face, eyes, and respiratory muscles (sensory symptoms are less pronounced than weakness)

Onset is over the course of days with rapid progression to possible quadriplegia in a few days, with maximum weakness achieved in 2-4 weeks

Hyporeflexia or areflexia

Neuropathic pain in lower back and thighs

Autonomic involvement, such as tachy/bradycardia, hyper/hypotension, gastric hypomotility, and urinary retention

70% of cases are preceded by respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. Less common precipitants are pregnancy, vaccination (controversial), surgery, or cancer

⊙ CLINICAL PEARL

Often the reflexes in GBS are absent in the setting of initially mild or moderate weakness - if someone is already paralyzed, reduced reflexes may not offer much information since some strength in a muscle is necessary for a reflex. However, if someone has 4/4+ strength but absent reflexes, this suggests a demyelinating process

GBS Variants

Acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN)

Acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN)

Miller-Fisher syndrome (Triad of ophthalmoparesis, ataxia, and hyporeflexia)

Paraplegic variant

Pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant

Red flags for other causes (not GBS)

HIV

Rash

Severe pain

Pupillary involvement

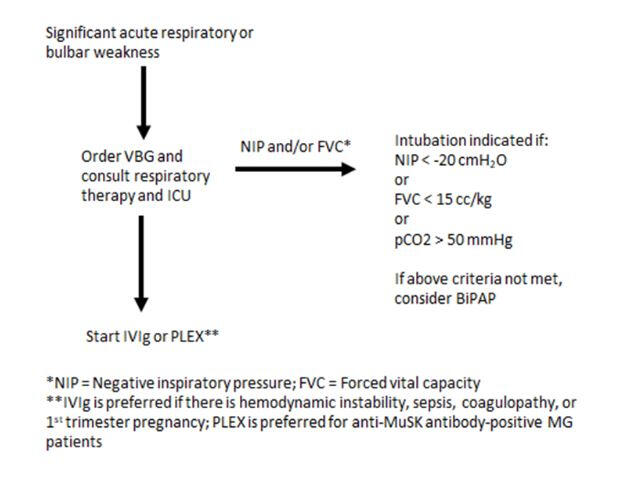

Investigations